As a child, he was a happy little fellow, and like most little boys looked forward to challenges and was interested in everything around him. When Irving and I moved into our first house, a modest semi-detached bungalow in Richmond Hill, (sale price: $12,500) it was a new subdivision, with deep ditches at the roadsides in front of the homes. At nine years of age he would disappear into those ditches looking for frogs.

Yesterday would have been my younger brother's 72 birthday had he lived beyond 65, the very year he retired as a professor of botany and ecology at Dalhousie University. He was a tenured professor, hired from his graduation date at University of Toronto so long ago. He was an activist advocate for the Nature Conservancy of Canada and he took his turn on their board for years.

Billy had a lifelong fascination with birds, an indefatigable bird-watcher. He would go to great geographical distances to be able to observe birds in their natural habitat, though at one time he kept his own little coterie of lovebirds and was focused on breeding them.

In his search to expand his bird list he went from the Arctic regions of Canada abroad to tropical regions of the world.

When he was in his teens it was reptiles that fascinated him. Our mother, who would brook no nonsense from any of us, had no patience for matters extraneous to existence in a hard world, made no protest when he assembled a collection of reptiles. When he was a little older he kept a raccoon in the house, free to go wherever it liked.

The plight of species under pressure eventually reached his consciousness and that became another issue to engross his interest. All fairly common concerns for any biologist.

:format(jpeg)/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/WF74VAB3XNDMTJXQY5VGYH2JQU) |

Professor Bill Freedman advised anyone with influence over children to encourage them to serve as stewards of nature.Mike Dembeck/The Canadian Press |

He had the added distinction of uprooting all the grass on his front lawn and replacing it with native species of vegetation. He would boast that his Jack-in-the-Pulpits were larger and taller than mine, which I had transplanted from our nearby ravine.

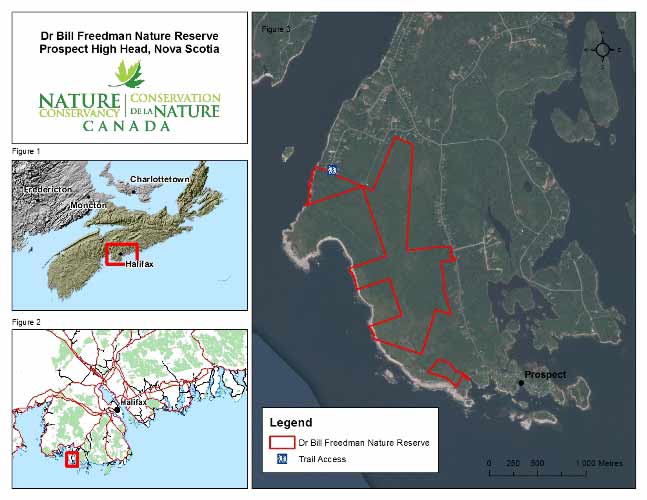

My junior by thirteen years, he informed me seven years ago that he had been diagnosed with late-stage stomach cancer, too late for any therapeutic interventions. In his memory the Nature Conservancy named a local area after him to honour his work on their behalf.

"First, collect and establish native shrubs in your existing yard. Ask around at nurseries, until recently nurseries did not have any native plants, and many still don’t.""It’s a good idea to research any plant you find to make sure it is native. It's not so important that the plant be native to precisely the area you live in, as long as they are native to the general area.""You can also get native plants from the surrounding countryside; again do some research to make sure the species is native, and of course make sure that it is abundant in the area you are taking it from. You can also start some species from seed."Advice: Botanist Bill Freedman

No comments:

Post a Comment